It’s been two weeks since the US federal elections (3-November), and the drama and noise continue. While still too early to have a thorough understanding of the methods and impact of disinformation in the campaign, it is clear that disinformation is shaping perceptions of the results. And there are strong signals, that unlike the 2016 election, disinformation was more of a US domestic operation than a foreign interference operation. In this post, we’ll look at early disinformation signals from both US and Russian disinformation sources.

For US disinformation, we’ll use a collection derived from newly registered domains (NRDs). The source of the collection is LookingGlass Cyber Solutions (full disclosure: LookingGlass is my employer). The LookingGlass NRD service monitors new domain registrations and updates from domain registries and applies term or regular expression matching to filter results for a particular subject, in this case, elections. For Russian disinformation we’ll use a collection from EUvsDisinfo, a European media research organization that monitors pro-Kremlin disinformation.

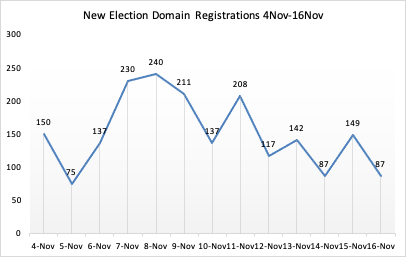

US Disinformation: The first thing we noticed was the post-election spike in the volume of election-related NRDs. For the 13-day period prior to the election (21Oct – 2Nov) there were 1,102 NRDs. This increased 79% to 1,972 registration for the 13-day period after the election (4Nov – 16Nov). Figure 1 shows total daily registration volume for election related NRDs for the post-election period. As we can see, election domain registrations rose sharply the first week, peaking on 8-Nov, and declining since.

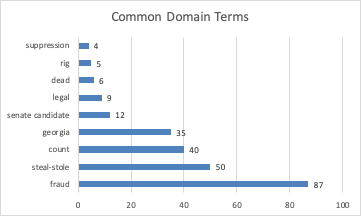

The next step was to filter the list for domains whose semantics matched popular disinformation themes, and whose domains were activated, i.e. the domains resolved to a working website. Filtering on disinformation themes, we identified 248 domains. Figure 2 shows the frequency of the terms or concepts that were chosen for their disinformation semantics.

Of these 248 disinformation domains, 186 (75%) were either parked or inoperative. This left us with 62 active domains that we classified as potentially disinformation based on the domain semantics. Of these domains, we observed the following:

- 5 (8%) of the domains are classified as Malicious based on submissions to the Hybrid-Analysis (CrowdStrike) scanner / sandbox

- 18 (29%) could be classified as Disinformation based on content that is demonstrably false and designed to deceive

- 28 (45%) of the domains have a Red political orientation, i.e. promoting Trump or GOP

- 6 (10%) of the domains have a Blue political orientation, i.e. promoting Biden or Democrats

- 18 (100%) of the disinformation orientation is Red.

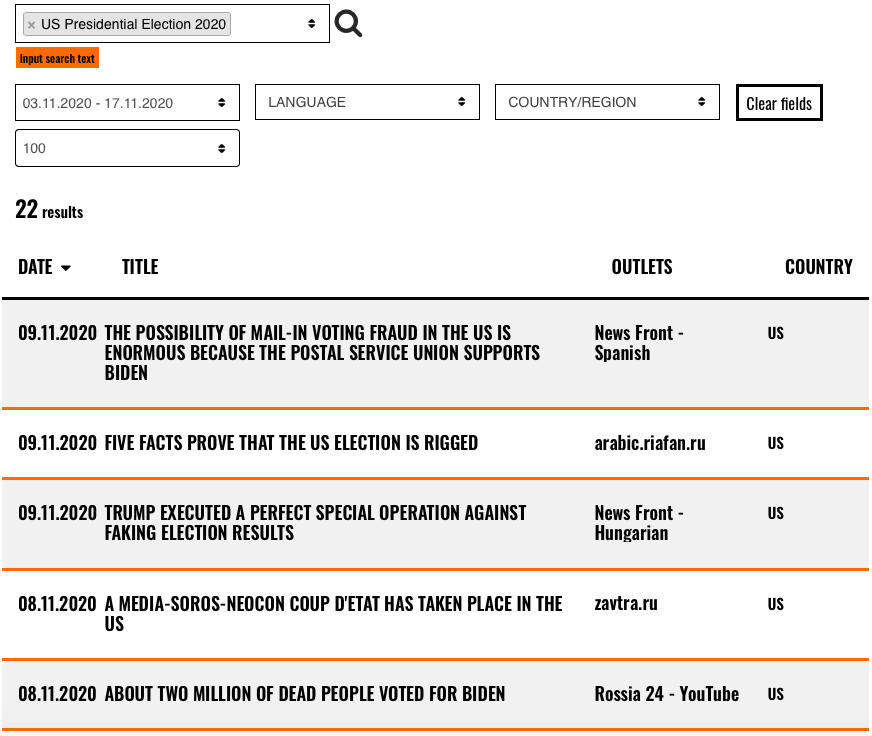

Russian Disinformation: One of the findings from the 2016 US presidential election was that Russian disinformation campaigns directly targeted US audiences. In response, election defenders and social media platform companies were primed to look for indications of foreign interference in the US elections. Based on the collection (EUvsDisInfo) and the time-period (post-collection) we analyzed, we found 22 Russian disinformation campaigns featuring the US presidential elections, but these campaigns were not targeting US audiences.

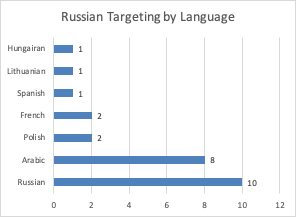

Figure 3 shows results for 5 of 22 Russian disinformation campaigns for the post-election period. Figure 4 shows the language targeting of these campaigns. What’s clear from this is English language audiences were not targeted. When we take a closer look at the language targeting and messaging, we can infer:

- Russia is targeting 4 audience segments; the largest of these is the Russian speaking population in Russia and Eastern Europe (10), followed by the Middle East (8), Central and Eastern Europe (4), and Western Europe (3)

- If there were a common messaging theme, it would be a familiar refrain – the US is corrupt, decadent and diminished.

Loose Ends: It’s dangerous to draw conclusions on recent or active events, so these findings should be considered preliminary. And the sources and sample sizes are small and limited to what we have access to. Nevertheless, we tried to let the data guide the analysis and we hope that the insights can spark further research by others. So with these qualifications, here are a few final comments:

- Social Media disinformation sources: Our US data was limited to domains for websites. A more rigorous analysis should also consider social media disinformation.

- Domain Registrars: As we have seen in our coronavirus disinformation analysis, domain registrars promote and profit from speculation in domain names even when those domains clearly facilitate disinformation. For example, 75% of the domains registered are not in service and were likely registered by speculators. Additionally, 56% of these domains were registered through GoDaddy. If regulators are looking at the responsibilities of social media platforms for operating ‘lawful’ environments, it seems reasonable to also look at the role of dominant registrars and hosting companies.

- Domestic Disinformation: Our preliminary analysis suggests that the story of this election was the influence of domestic disinformation, and the overwhelming evidence of red-leaning orientation. While we found no indications of foreign interference targeting US audience, we did find evidence of Russian disinformation amplifying domestic disinformation themes (fraud, mail-in voting, dead-people voting, rigged elections) in their campaigns, the goal of which is to undermine confidence in democracy, the West and the US.