Welcome to the first edition of the ThreatShare Sector Spotlight Series! Batting lead-off is the Water and Wastewater Systems (WWS) Sector. But first, a few words about our new series.

The Sector Spotlight Series is motivated by ThreatShare’s commitment to Generative AI (GenAI) for Cybersecurity and Cyber Threat Intelligence (CTI), and our previous experience supporting the DHS Critical Infrastructure Sector program and Information Sharing and Analysis Centers (ISACs). As CTI practitioners, we understand that context – along with relevance, accuracy, timeliness – makes tactical, operational, and strategic intelligence effective. Practical knowledge of industry sectors is an essential aspect of context. Our goal is to demonstrate a method and model for building a sector classification data collection and using it to improve the effectiveness of cyber threat intelligence.

Sector classification is a nuanced and inherently subjective discipline within data science. It involves fusing multiple industry classification taxonomies, from broad taxonomies like DHS CISA’s Critical Infrastructure Sector model of 16 sectors, to more granular models like the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics based on the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS).

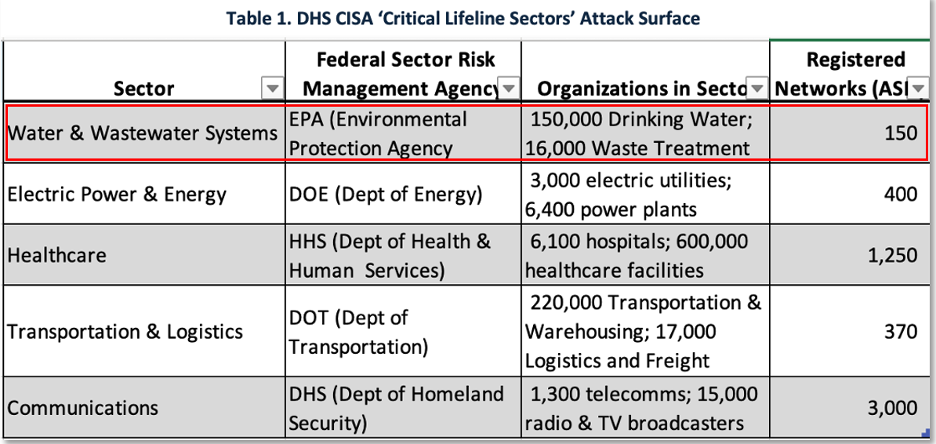

For our Sector Spotlight we will start with the four CISA Lifeline Sectors: water, energy, communications, and transportation. Some models also classify healthcare as a lifeline sector. Lifeline Sectors are sectors whose reliable operations are so essential that their disruption could have a cascading effect on other sectors and directly affect the security, economy, public health, and safety of the country. A summary of selected statistics for our lifeline sectors is shown in Table 1.

Our analysis is enabled by original research and development of a sector classification method and model. For our test data, we used network registration data for 18,000+ Internet networks in the U.S. as measured by (Autonomous System Numbers – ASNs), and derived from open source BGP (Border Gateway Protocol) data. We enriched the data using sector classification prompts in our custom ‘ThreatShare Cyber Researcher,’ an implementation of OpenAI’s ChatGPT 4o. The GenAI sectorization process generated close to 100 unique sector classification data labels for each ASN in the data collection. After extensive human analyst review, we reduced this to 40 sector labels.

Notes:

- All numbers are rounded estimates as of 1-17-2025

- ‘Organizations in Sector’ column was generated using GenAI and validated by ThreatShare against the EPA’s Safe Drinking Water System (SDWIS) database. [19]

- Sector classification is not binary. An organization may be classified in multiple sectors, particularly with respect to Water and Power, Water/Power and Communications, and Water/Power and State-Local Government.

Sector Attack Surfaces

In cybersecurity, an ‘attack surface’ encompasses all potential vulnerabilities within a digital infrastructure that adversaries might exploit. This includes both IT (Information Technology) systems and OT (Operational Technology) devices such as SCADA systems, HMIs, PLCs, IoT devices, user accounts, and third-party dependencies. [2] The scope of an attack surface can be applied to an organization, a supply-chain, an industry sector, a geographic area, and even a country. Attack surface metrics are essential to ‘Fundamental 1 – Perform Asset Inventories’, of the WaterISAC cybersecurity model. [3]

Methods and tools for Attack Surface discovery are well known and used by both cyber defenders and attackers. For example:

- Tools like Shodan, Censys, and Google Dorks are integral to the cybersecurity toolkit, enabling the discovery of IT networks and ICS (Industrial Control System) devices. For example, we used Shodan to discover over 30,000 IPs in the U.S. with HMI devices, including devices used by small water utilities. CISA has issued multiple alerts over the past year on adversarial use of these tools for OT asset discovery on IT networks. [11,12].

- DNS intelligence tools, such as Silent Push, facilitate network infrastructure discovery, proactive threat hunting, and the identification of phishing attacks impersonating Water Sector companies or vendors.

- Dark Web Intelligence tools are used to discover compromised email accounts for utility companies and their third-party service providers, dedicated leak sites of ransomware victims, and specialized forums and marketplaces.

In Table 1, Columns 3 and 4 represent quantitative metrics on the scale of the WaterISAC attack surface. Among Lifeline Sectors, the Water Sector ranks second in the number of organizations (~165,000) but has the fewest large organizations (~150) operating their own IT and OT networks. This represents only 0.09% (150/165,000) of the organizations in the sector. The remaining 99% of the organizations can be enumerated using SDWIS data and passive asset discovery methods as described above.

The ‘target rich, resource poor’ state of cybersecurity in the Lifeline sectors, and in particular the WWS Sector, is recognized by the EPA, CISA, and leading sector-focused cybersecurity service provides like Dragos and IST (Institute for Security & Technology) [6-8]. The sector suffers from reliance on legacy and inherently insecure technologies, limited cybersecurity expertise, and insufficient economic resources.

To address these issues, CISA provides funding, information sharing and analysis centers (ISACs), and technical services like the Cyber Hygiene Vulnerability Scanning service designed for small organizations in the Lifeline sectors. Recent results show promise in terms of reductions in visible and exploitable services, and vulnerability resolution time. While participation in the CISA program has increased by 240% over the past two years, overall engagement remains low. [4,5] Given the knowledge and resource limitations of small utilities, this suggests a need, and opportunity, for organizations like the WaterISAC and managed security service providers (MSSPs) to address these issues.

Cyber Threat Landscape

This section highlights key features of the cyber threat landscape affecting the Water and Wastewater Systems (WWS) sector. For authoritative and comprehensive sources of current and historical reporting, we recommend data and analysis from the WaterISAC, the EPA – the Sector Risk Management Agency (SRMA) for the Water Sector, DHS CISA, and other sources listed throughout this report and in the References section.

While this post focuses on cybersecurity in the Water sector, it is important to note that the cyber domain is just one of many domain features of the environment, along with geographic, natural disasters, political, economic, regulatory, demographic, social, and geopolitical domains. As these other domains shape the cybersecurity domain, we begin with a look at some of the inherent characteristics of the sector. Many of the characteristics described below also apply to other lifeline sectors.

Inherent Characteristics

- Scale and Structure: As noted in Table 1, with more than 165,000 organizations the sector is vast and comprised of different types of organizations (small privately owned, large publicly traded, state and local government, regulated utilities). To illustrate the structural characteristics, we analyzed EPA data from 524 Community Water Systems (CWS) in Massachusetts. [20] Of these 79% (412/524) supported populations of less than 20,000 and could be classified as small. This is consistent with Barracuda Networks recent report that ‘92% of community water systems are small public water systems (PWSs) serving fewer than 10,000 customers’. [23]

- Decentralized and remote operations: Water utility operations are highly decentralized, spanning large geographic and rural areas. Using our EPA Massachusetts data collection, we determined that the mean number of facilities per CWS is 11. The operations involve various facility types including water treatment plants, wastewater treatment plants, pump stations, storage facilities, and distribution and collection systems. Many facilities are unattended, remotely managed, and reliant on telecommunications, power providers, and emergency services. While all operators need to monitor physical and cybersecurity and provide situational awareness, each operator may use different types and makes of systems, including: ICS (Industrial Control System) devices (SCADA, HMIs, PLCs) to monitor, sense and regulate pressure, levels, flow, chemicals; IoT devices (security cameras, gates, environmental controls); and network devices (VPNs, firewalls, routers, remote access).

- Systems: The systems and technologies used to operate these systems are complex. Many are old, insecure, and easily compromised.

- Personnel Skills: It is generally believed that the cybersecurity skills in the sector are limited.

- Economics: With mostly small and community operated by local governments, the sector depends on federal government for funding and technical advisory services.

Challenges

- Cyber-physical system (CPS) attacks are costly: According to a Claroty survey (October 2024) of 1,100 cybersecurity professionals, 45% of organizations reported financial impacts exceeding $500,000 from CPS-targeted cyberattacks, with 27% incurring losses over $1 million. [9] An IBM report published 10-Jan-2025 estimates attacks on the industrial sector average $5.56 million. [10]

- 9.7% in sector either critical or high-risk cybersecurity vulnerabilities: U.S. Scan results of 1,600 drinking water systems for October 8, 2024, identified 97 drinking water systems serving approximately 26.6 million users as having either critical or high-risk cybersecurity vulnerabilities. EPA Report Nov 2024[17]

- CISA-EPA Exposed and vulnerable HMIs: Dec 2024 Notice recommends limiting the exposure of HMIs on the internet and securing them against malicious cyber activity operators. [11]

Vulnerabilities

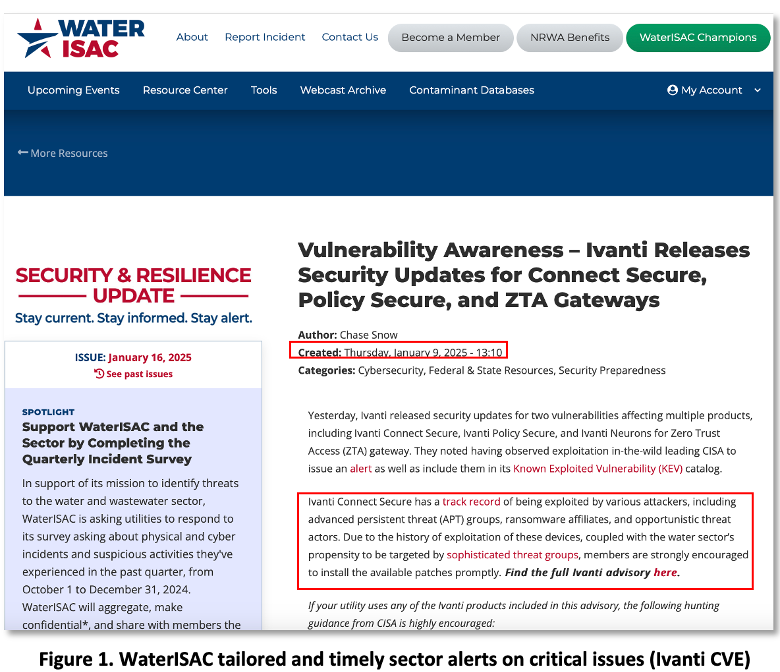

- Ivanti CVE-2025-0282 and 0283 Jan 2025. See: WaterISAC Jan 9 Alert (see Figure 1), Ivanti Disclosure, Palo Alto Networks and Mandiant threat briefs, Censys exposures update, and CISA Mitigation Instructions. [24-28]

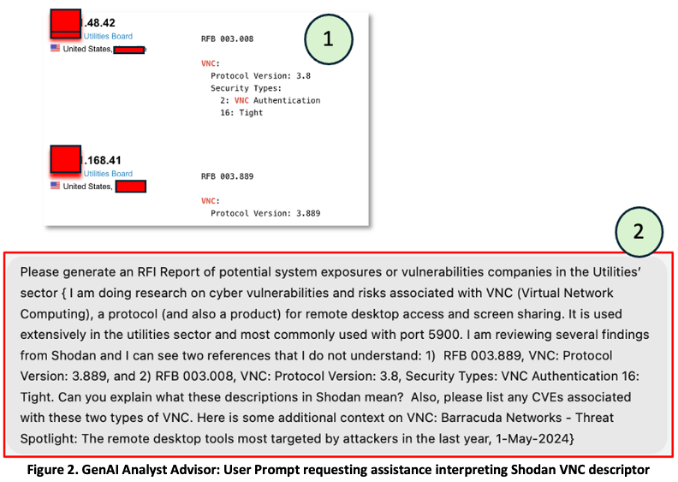

- ThreatShare Shodan VNC search for VNC, using port 5900, in the U.S. generates > 30,000 results; preliminary review identified 7 water utilities and > 25 devices. See Figures 2 and 3.

- ThreatShare Shodan VNC search for Unitronics in the U.S. generates 29 results

- ThreatShare ‘filtered search’ of the CISA Advisories and Alerts data for 2024 in ‘Water and Wastewater Systems sector’ database finds 30 Alerts or Advisories.

- ThreatShare filtered search of CISA’s Known and Exploited Catalog (AKA KEV list) for ‘ICS’ devices generates 29 CVEs for relevant vendors/products including Unitronics PLC, Schneider Electric, Siemens SIMATIC, Ivanti Connect Secure and more.

- Barracuda Networks – Threat Spotlight: The remote desktop tools most targeted by attackers in the last year: vulnerabilities in software widely by utilities (VNC – Virtual Network Computing) shows 60% of malicious traffic targeting VNC from China. [22]

Adversaries

The cyber adversary landscape targeting the Water Sector includes nation-state actors, national hacktivist or patriotic hackers, and cybercriminals. The examples below are drawn from authoritative sources like WaterISAC (TLP:Amber), Barracuda Networks, ReliaQuest, and the EPA. [12, 18, 20, 21, 30]. The Water ISAC report maps 13 attacks against the WWS sector in 9 states from 23-Nov-2023 to 22-April-2024.

State-sponsored actor – China: Volt Typhoon (AKA Vanguard Panda): Considered the most serious threat group. Gains initial access using spearphishing and compromised credentials. Often targets vulnerable network devices like Fortinet, Ivanti, NETGEAR, Citrix, and Cisco. Following compromise, the actor uses RDP and LOTL (Living off the land) methods to move laterally. The actor has demonstrated exceptional operational security (OPSEC) and long dwell times, remaining undetected in networks for years. Has compromised information technology (IT) in critical infrastructure systems, including the WWS sector. CISA Alert AA24-038A 7-Feb-2024 indicates that Volt Typhoon has burrowed deep in networks and is prepositioned for launching destructive attacks in the event of geopolitical tensions and/or military conflicts. [31]

State-sponsored actor – Iran: Iranian Government Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) AKA CyberAv3ngers: Has attacked OT in the U.S. WWS Sector (Aliquippa PA and Vero Beach FL) as well as utilities in Israel. Targets Israeli-made Unitronics PLCs and HMI using manufacturer default passwords. Unconfirmed reports of collaboration with other threat groups including Hunt3r Kill3rs and the Cyber Army of Russia Reborn (CARR). See CISA Alert AA23-335A 18-Dec-2024. [32]

Russian State-sponsored Affiliates: Barracuda Networks 26-Dec-2024 Report on attacks targeting the water sector identifies Russian hacktivist groups – People’s Cyber Army (PCA), Z-Pentest, and Cyber Army of Russia Reborn (CARR) – that operate as affiliates of the Russian threat actor Sandworm, AKA ‘GRU – Military Unit 74455’. Barracuda attributes CARR attacks on water systems in Texas (Muleshoe, Abernathy, Hale Center, and Lockney) as geographically proximate to Cannon Air Force Base, home to U.S. Air Force Special Operations Command and the 27th Special Operations Wing. [21] We are also seeing evidence of Russian hybrid warfare campaigns – blending physical, cyber, and narrative, tactics – in Finland and Germany. See CISA – EPA Advisory: Internet-Exposed HMIs Pose Cybersecurity Risks to Water and Wastewater Systems, 10-Dec-2024.

Cybercriminal Groups: Top 5 Ransomware Groups: LockBit, Play, ALPHV/BlackCat group, Akira and 8base. [12]

Incidents

Selections from ReliaQuest Threat Landscape Report: Uncovering Critical Cyber Threats to Utilities, 10-Dec-2024

- Ransomware attacks against utilities increased by 42% over the past year, with 75 utilities posted to ransomware leak sites during the study period

- 81% of all attacks involve spearphishing.

While most of the reported incidents were against small or municipal water utilities, two large commercial providers in the WWS sector also reported attacks. In January 2024, Veolia North America disclosed a ransomware incident, and in October 2024 American Water Works filed a breach disclosure to the SEC. Neither of these attacks impacted OT networks or water systems.

GenAI for Water Sector

Generative AI (GenAI) offers virtually limitless potential for enhancing cybersecurity in larger organizations within the water sector. Applications can be found for any business function or any function within the cybersecurity operation (CISO). They can be used with APIs as agents for automation, or interactively as research assistants, or on-demand tutors. However, their use requires human oversight due to well-known issues with accuracy and data leaks.

In this section, we provide examples of two interactive analyst assistants. We are using our custom ‘ThreatShare Cyber Researcher’ implementation of OpenAI’s ChatGPT 4o’, which we have trained using thousands of system prompts for the cyber threat intelligence domain, and data sources that provide domain context for the water sector.

Use case 1 – interactive cyber analyst assistant: As previously noted, Russian patriotic hackers, and many other threat actors, use tools like Shodan or Censys to discover vulnerable versions of VNC in order to access HMIs that they can exploit. [33] Figure 2, panel 1, displays a partial, redacted section of Shodan results for VNC hosts in the WWS sector. In our scenario, a diligent cybersecurity team for a MSSP (Managed Security Service Provider) or large organization in the WWS sector heeded CISA guidance to harden HMI access points and VNC. An analyst tasked with identifying exposed VNC devices within their area of interest could use Shodan for this purpose. However, the analyst might have trouble understanding the arcane technical descriptions of various VNC devices and configurations. As seen in panel 2 of Figure 2, the analyst, realizing that this would be a good application for the ‘interactive cyber analyst assistant’ created a detailed prompt, providing the GenAI chatbot with relevant context.

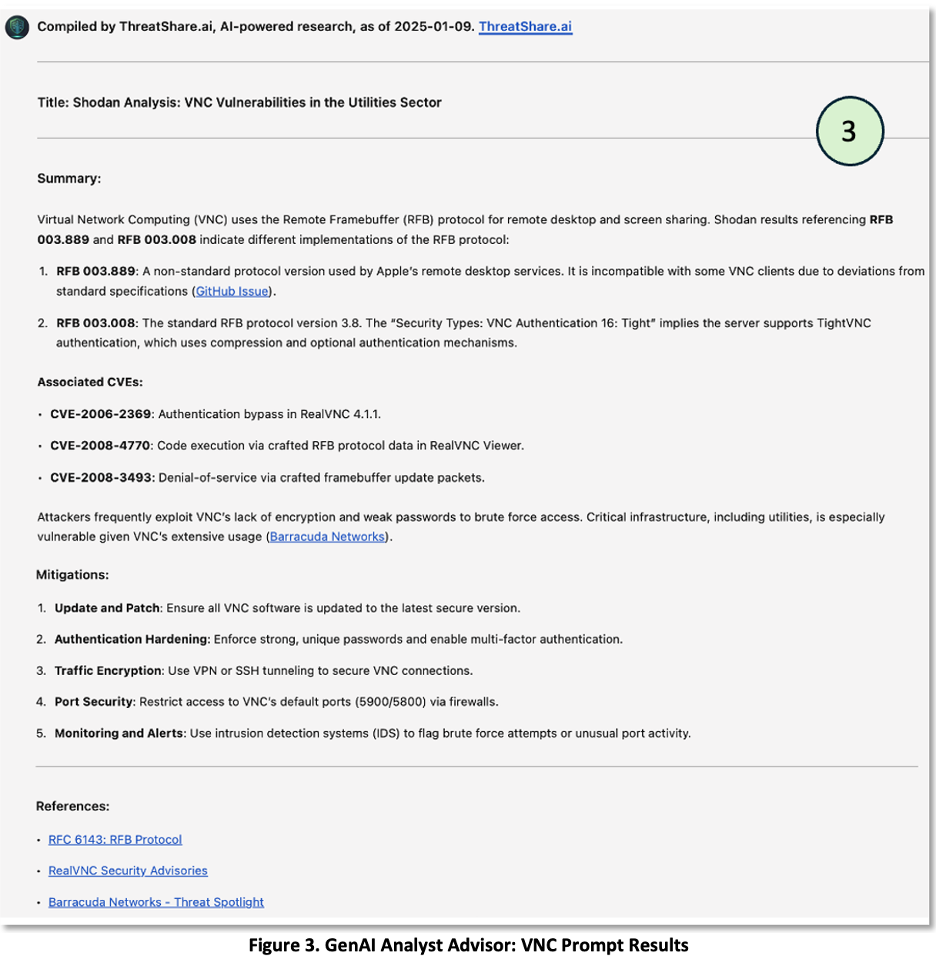

In Figure 3, panel 3, we see results generated by the ThreatShare chatbot. Using the references in the results, the analyst is able to verify the accuracy of the results. The Chatbot satisfied the RFI quickly and appropriately, and the analyst did not have to go for help.

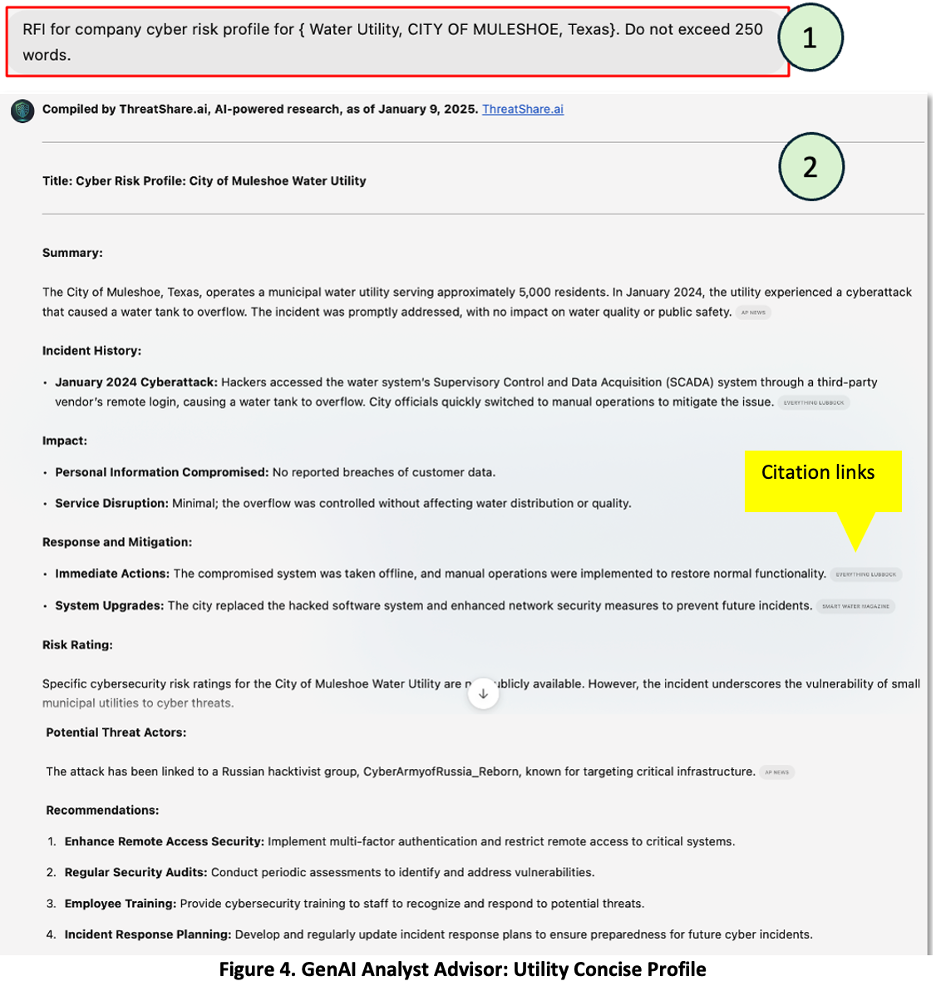

Use case 2 – interactive cyber analyst assistant: In the next scenario as shown in Figure 4, the analyst has an RFI to write a cyber risk profile for a small water utility in the City of Muleshoe, Texas. Since RFIs for cyber risk profiles are a common task for this agent, a senior analyst developed a detailed system prompt – nearly 1,000 words – defining the report structure, format, and instructions.

These complex system prompts enable junior analysts to generate a full cyber risk profile with a simple 18 word user prompt as shown in Figure 4, panel 1. In Figure 4, panel 2, see the Chatbot results for the city of Muleshoe. Note the reference to the previous attack by Russian patriotic hackers and the supporting citations. With 165,000 organizations in the sector, the ability to rapidly generate concise reports on demand would be an invaluable tool for oversight organizations and cyber risk teams.

Outlook

The increasing sophistication of nation-state adversaries, combined with the growing use of adversarial AI, suggests that cybersecurity threats will continue to escalate.

Countering this threat will require:

- Developing more effective cyber threat intelligence informed with sector intelligence

- Better understanding of the complex attack surface

- Strengthening information sharing within the WWS sector and across other lifeline sectors (e.g., Communications and Power), and with international allies

- Improving sector cyber situational awareness

- Strong proactive threat-hunting solutions are needed to address spearphishing attacks, which are used in 81% of attacks against the utilities sector

- Greater roles for Managed Security Service Providers (MSSPs) and Sector and Cross-sector Information Sharing led by groups like CISA and the WaterISAC

- Broad adoption of GenAI across the cybersecurity organizations

Proactive measures and collaboration are essential to defend the WWS sector against the increasingly sophisticated cyber threats of the future.

Editor’s Notes:

- Acknowledgment to our chatbots for their valuable support in sector classification, threat analysis research, proofreading, and editorial review

References

- CISA – Critical Infrastructure Sectors

- NIST – NIST Special Publication 800-160, Volume 2 Revision 1 – Developing Cyber-Resilient Systems: A Systems Security Engineering Approach, Dec-2021

- Water-ISAC – 12 Cybersecurity Fundamentals for Water and Wastewater Utilities, December 2024

- CISA – Cross-Sector Cybersecurity Performance Goals, January 2025

- EPA Cybersecurity for the Water Sector, last updated 13-Dec-2024

- IST (Institute for Security & Technology) – UnDisruptable27: Driving More Resilient Lifeline Critical Infrastructure for Our Communities

- Dragos – OT Cyber Threat Landscape for the U.S. Water & Wastewater Sector , 17-April-2024

- Claroty – SURVEY REPORT The Global State of CPS Security 2024: Business Impact of Disruptions, October 2024

- IBM Security Intelligence – https://securityintelligence.com/articles/is-the-water-safe-state-of-critical-infrastructure-cybersecurity/, 10-Jan-2025

- CISA – EPA Advisory: Internet-Exposed HMIs Pose Cybersecurity Risks to Water and Wastewater Systems, 10-Dec-2024

- CISA – Joint Advisory: Defending OT Operations Against Ongoing Pro-Russia Hacktivist Activity, 1-May-2024

- ReliaQuest Threat Landscape Report: Uncovering Critical Cyber Threats to Utilities , 10-Dec-2024

- EPA Factsheet – Top 8 Cyber Actions for Securing Water Systems, March 2024

- Water-ISAC – Cyber Resilience – Cybersecurity Challenges Facing Water Utilities , 2-Jan-2025

- CISA – Water and Wastewater Toolkit: https://www.cisa.gov/water

- EPA-OIG – Report No. 25-N-0004: Management Implication Report: Cybersecurity Concerns Related to Drinking Water Systems, 13-Nov-2024

- EPA Office of Water – EPA Guidance on Improving Cybersecurity at Drinking Water and Wastewater Systems, Revised August 2024

- WaterISAC – TLP Amber Report: Threat Analysis for Water and Wastewater Sector, 30-Sept-2024

- EPA (SFDWIS): Safe Drinking Water Information System

- Barracuda Networks – Threat Spotlight: The remote desktop tools most targeted by attackers in the last year, 1-May-2024

- Barracuda Networks – Infrastructure defense: Water and wastewater systems, 26-Dec-2024

- EPA – Information about Public Water Systems, 30-Oct-2024

- Ivanti – Security Advisory Ivanti Connect Secure, Policy Secure & ZTA Gateways (CVE-2025-0282, CVE-2025-0283), Created 8-Jan-2025, Update 21-Jan-2025

- WaterISAC – Vulnerability Awareness – Ivanti Releases Security Updates for Connect Secure, Policy Secure, and ZTA Gateways, 9-Jan-2025

- Palo Alto Network – Unit 42: Threat Brief: CVE-2025-0282 and CVE-2025-0283 (Updated Jan. 17) , 17-Jan-2025

- Google – Mandiant: Mandiant: Net Connect Secure VPN Targeted in New Zero-Day Exploitation, January 8, 2025

- Censys – January 10 Advisory: Actively Exploited Unauthenticated RCE in Ivanti Connect Secure [CVE-2025-0282], update 13-Jan-2025

- CISA – CISA Mitigation Instructions for CVE-2025-0282

- American Water Works – American Water Works Breach Filing to SEC, 10-Oct-2024

- EPA – EPA letter to State Governors , 18-March-2024

- CISA: Cybersecurity Advisory, Alert Code AA24-038A – PRC State-Sponsored Actors Compromise and Maintain Persistent Access to U.S. Critical Infrastructure, 7-Feb-2024

- CISA: Cybersecurity Advisory, Alert Code AA24-335A – IRGC-Affiliated Cyber Actors Exploit PLCs in Multiple Sectors, Including US Water and Wastewater Systems Facilities, 18-Dec-2024

- CISA – Defending OT Operations Against Ongoing Pro-Russia Hacktivist Activity, 1-May-2024