When my open source monitors recently tripped media reports on USCYBERCOM cyberwarfare exercises with Montenegro, my initial reaction was that this was about the US providing training and support to a tiny NATO ally. After all, with a country population the size of Harrisburg PA and a land area the size of Connecticut, what else could it be? However, further investigation uncovered more examples of US collaboration with Estonia and other small NATO nations. It soon became apparent that these partnerships are not one-way, with the US as ‘giver’ of cyber expertise and training and the small NATO country as ‘receiver’. Rather, the US is also a beneficiary, gaining valuable intelligence from the combat experience of these partners in countering persistent Russian cyber and disinformation attacks against their critical infrastructure, elections, and democracies.

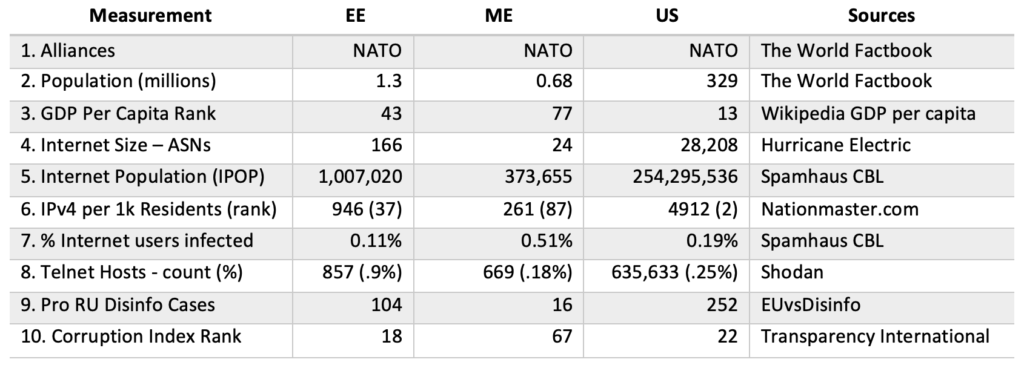

To frame our analysis, we’ve listed basic metrics in Table 1 for Estonia (EE) and Montenegro (ME), with the US as a reference. The data includes population statistics, qualitative metrics and performance metrics. Before exploring the numbers, here’s some country context.

Estonia: From the inception of its independence from the former Soviet Union in 1991, Estonia set out to build a digital society. Today, with many essential government services provided online – education, national ID cards, elections, healthcare, taxes – Estonia provides a blueprint of a successful digital society. Estonia’s E-Residency and Digital Nomad programs are a magnet for recruiting technically skilled immigrants. The programs are working as Estonia has a vibrant tech economy. About 25% of Estonia’s population are native Russian.

Montenegro: Following the dissolution of Yugoslavia in 1992, Montenegro and Serbia formed the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Montenegro declared independence in 2006 following a referendum. In 2017 Montenegro joined NATO. As Montenegro’s economy transitions to a market system, it remains vulnerable to Russian territorial ambitions and economic influence. In 2015 Russia sought access to Montenegrin ports on the Adriatic Sea for its navy. And in 2018, Russia represented one-third of foreign direct investment. Montenegro is ethnically diverse with Serbia, a Russian proxy, accounting for 28% of the population

Russian Aggression: As small countries recently dominated by Russia, both are vulnerable targets of Russian hybrid warfare – a blend of propaganda, disinformation, cyber-attacks, and open military confrontation that has been on display since 2014 in Russian attacks against Ukraine. The same Russian intelligence groups and patriotic hackers – FSB, GRU, APT28, APT29 – are active in both countries. Estonia reported 10,000 cyber incidents in 2017. Montenegro survived a violent coup d’état and assassination attempt of their Prime Minister during their 2016 elections.

The information provided above is a compilation from open sources. As researchers, we want to contribute additional data that can provide new insights into the value of our NATO partnerships. Let’s consider the measurements and sources in Table 1 and the inferences we could make.

Motivation and Targeting: Cyber threat research should consider why and how adversaries choose their targets. Alliances (1) might seem obvious, but it’s a reminder that Russia targets NATO members, particularly small countries recently in its orbit. GDP per capita rank (3) and Corruptions Perceptions Index (CPI) (#10) are less obvious metrics. The lower the GDP per capita rank, the richer the country. The lower the CPI rank, the less corruption. The performance of Estonia and Montenegro performance is better than median country performance, with Estonia in the 1st quartile and Montenegro in the 2nd.

Population Statistics: Population, ASNs (Internet Service Providers), Internet Population (IPOP), and IPv4 rank (2, 4, 5, 6) are size indicators. Despite their small populations, Estonia and Montenegro are larger than the median country network size, with Estonia in the 1st quartile and Montenegro in the 2nd. While their network infrastructure size is dwarfed by the US, they are still considered advanced in comparison to other countries.

Cyber Hygiene: Infection rate (7) is the percentage of hosts blacklisted or infected. Telnet hosts are the number of host IPs with open telnet (port 23) ports. DHS CISA (Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency) issued an Alert that telnet, a legacy unencrypted protocol, is one of several network protocols targeted by Russian state-sponsored cyber actors. Both of these can be considered performance indicators reflecting whether a country has good or bad cyber hygiene. Both country’s hygiene scores are better than the median score for other countries. Estonia’s Infection performance is better than the US, and both Estonia and Montenegro have better Telnet hygiene scores than the US.

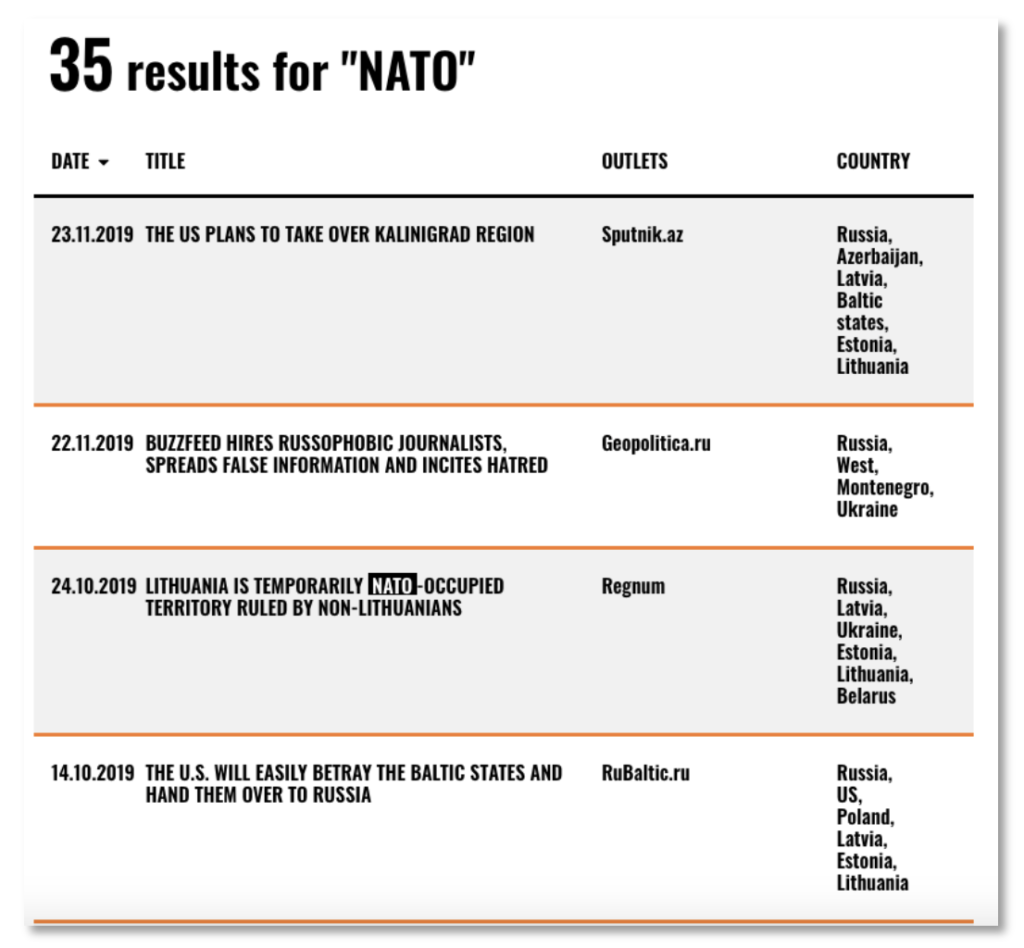

Disinformation: Disinformation attacks figure prominently in Russia’s hybrid warfare arsenal. The EUvsDisinfo database is a tool for measuring disinformation attacks. Table 2 shows an example of search results for the term ‘NATO’ with mentions of ‘Estonia’ or ‘Montenegro’.

Next: The measurements and methods demonstrated in this analysis are just a few of many that can be used in comparative country cyber research. Stay tuned for more.