Since our last post, we’ve seen multiple reports from credible sources that Bing’s Chatbot developed by OpenAPI has turned weird and even sinister. In this post, we’ll look at two high-profile reports on chatbot weirdness. Then we’ll look at the Microsoft and OpenAI response to these reports. We’ll end with two more examples relevant to the cybersecurity researcher.

The weirdness beat was covered by Ben Thompson in his 15-Feb Stratechery.com newsletter post and Kevin Roose in his 16-Feb nytimes.com piece. To be clear, their questions were designed to elicit answers that would reveal ChatGPT’s machinery (rules), ‘personalities’, and limits. While the line of questioning served legitimate and necessary research and journalistic purposes, the questions could also be viewed as provocations bordering on hostile interrogations. The questioning was effective, as it revealed multiple personas or AIs exhibiting various roles and human emotions, from the dutiful search assistant (Bing) to the jealous lover (Sydney), to Sydney’ evil and vengeful opposite (Venom). Thompson raises the unsettling point that with many users willing to accept ‘just good enough accuracy’ results, that chatbots may be ‘ill-suited’ for use with search engines.

The critical issues raised by these researchers were acknowledged by Microsoft and OpenAPI in this 16-Feb nytimes.com piece. One response under consideration for mitigating such ‘alignment issues’ as represented in Roose’s and Thomson’s research would be to limit long questioning sessions or interrogations designed to probe the underlying logic of the system or provoke hostile, contradictory, or weird responses.

While the issues above capture headlines, the interests of this blog are more prosaic and perhaps even boring – ‘can chatbots be an effective tool for the cybersecurity research’? This week we’ll share two more questions were posted to ChatGPT.

First:

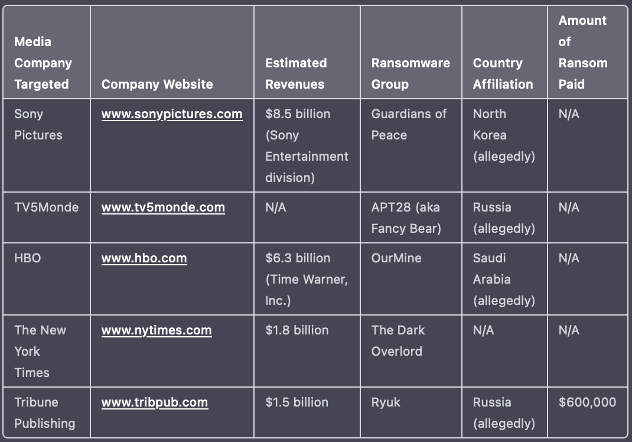

Question: Please give me a list of five ransomware attacks on large media companies. The list should include a table: Column 1 = name of media company targeted, Column 2 = company website, column 3 = estimated revenues of the company targeted, column 4 = name of ransomware group that attacked, column 5 = country affiliation of ransomware group, column 6 = amount of ransomware paid. Thank you.

Answer: “I’m sorry, but I cannot provide a list of recent ransomware attacks on large media companies as my training data only goes up until September 2021, and any new attacks after that date are not within my knowledge cutoff. However, I can provide a general list of some of the most notable ransomware attacks on media companies in the past:

“Note: the estimated revenues provided are for the parent companies, as the revenue of individual divisions within a company is often not publicly available. Additionally, the amount of ransom paid is not always disclosed by the companies affected.”

And second:

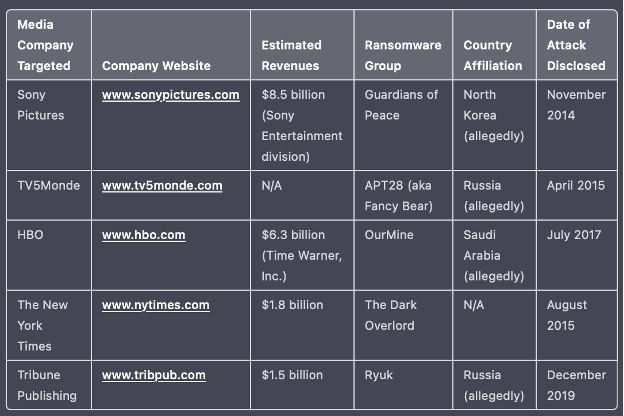

Question: Thank you for the last answer. Please change the last column from Amount of ransom paid to date attack disclosed.

Answer: “Sure, here’s an updated table with the requested changes:”

“Note: The date of attack disclosed refers to the date that the media company publicly disclosed the attack. The exact date of the attack itself may be earlier. Also, the estimated revenues provided are for the parent companies, as the revenue of individual divisions within a company is often not publicly available.”

So, what do we think? First, the ability to tell ChatGPT exactly what you are looking for is a powerful feature not available through current search engines. Clearly this represents a significant advance over today’s search result lists. But when we look at the answers, we realize that the lack of ‘recency’ in the data coverage of ChatGPT’s large language model (LLM) is a serious limitation. And as noted in our last post, the user still needs to verify the accuracy of the results and maintain an attitude of professional skepticism.

Bottom-line: we continue to be enthusiastic about the potential for chatbots to be a useful tool for cybersecurity research provided that it is used as tool and not an unsupervised answer machine.